How Not to be Eroded

How Not to be Eroded

READING ︎︎︎ E.M. Forster, A Passage to India

Jess Bernhart is a writer, curator and arts administrator. Currently managing rotating exhibits and special projects for ATL Airport Art, Bernhart also runs an artist publishing project, Volatile Parts, and an artist residency in Montezuma, GA, Volatile House.

Bernhart co-curates fLoromancy, a (currently hibernating) arts publication. She has published essays, poetry, and arts criticism in Burnaway, ArtsATL, Eyedrum Periodically, Loose Change, ++, and has exhibited visual art in a handful of group shows, mostly in Atlanta. She holds a bachelor’s in philosophy from Haverford College and a master’s degree from the London School of Economics.

Bernhart co-curates fLoromancy, a (currently hibernating) arts publication. She has published essays, poetry, and arts criticism in Burnaway, ArtsATL, Eyedrum Periodically, Loose Change, ++, and has exhibited visual art in a handful of group shows, mostly in Atlanta. She holds a bachelor’s in philosophy from Haverford College and a master’s degree from the London School of Economics.

There’s a wind chime on the neighbor’s porch — one of those standard models with hollow tubes and a wooden striker, the kind you find next to the seed packets at the hardware store, the kind that assumes its own neutrality. It’s easy to ignore. It blends in with the edge of things: the porch post, the hanging fern. And yet it insists, subtly, on a certain relationship to the world — a responsiveness structured by waiting.

It only makes sound in response to contact. That feels important. It does not initiate, but neither is it inert. The wind chime is a passive object until touched by something external — invisible, environmental — at which point it transforms, briefly, into sound.

It exists only partially. For long stretches, it is suspended, mute. Then, for a moment: sound. Then silence again. This rhythm — absence, interruption, resonance, absence — mirrors a rhythm I recognize in both motherhood and creative practice.

The wind chime models a kind of receptivity that’s rarely celebrated in a culture that prefers output, control, self-starting. But here is a form that does none of those things. It’s not an instrument one plays. It’s an instrument that allows itself to be played by the weather.

And maybe there’s something valuable in that — in a form that does not resist transience, that is shaped entirely by contact, and that understands its purpose as something temporary, ephemeral, and contingent.

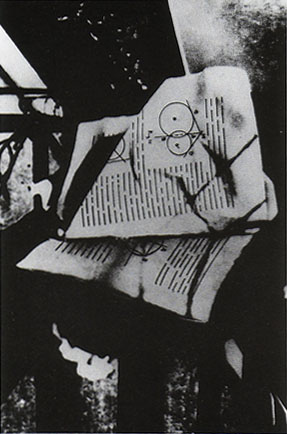

I think of Duchamp’s Unhappy Readymade, a geometry textbook hung outside in the elements for an extended period of time in 1910, in Buenos Aires. Perhaps the windchime is a subtle piece of conceptual art, smuggled into households as musical instrument, an artwork in disguise.

There’s also something architectural in it — a system of hollow parts, suspended, designed not for use but for possibility. A structure that makes no claim to permanence, but does insist on design. The wind chime is not chaos. It’s an ordered possibility. And the sound it makes is less a performance than a document: evidence of atmosphere.

This is not a grand metaphor. It’s just an object I keep passing and noticing — how it holds silence, how it responds, how it sounds and stops and sounds again. And how, like many structures I admire, it is defined not by what it produces, but by what it allows.

It only makes sound in response to contact. That feels important. It does not initiate, but neither is it inert. The wind chime is a passive object until touched by something external — invisible, environmental — at which point it transforms, briefly, into sound.

It exists only partially. For long stretches, it is suspended, mute. Then, for a moment: sound. Then silence again. This rhythm — absence, interruption, resonance, absence — mirrors a rhythm I recognize in both motherhood and creative practice.

The wind chime models a kind of receptivity that’s rarely celebrated in a culture that prefers output, control, self-starting. But here is a form that does none of those things. It’s not an instrument one plays. It’s an instrument that allows itself to be played by the weather.

And maybe there’s something valuable in that — in a form that does not resist transience, that is shaped entirely by contact, and that understands its purpose as something temporary, ephemeral, and contingent.

I think of Duchamp’s Unhappy Readymade, a geometry textbook hung outside in the elements for an extended period of time in 1910, in Buenos Aires. Perhaps the windchime is a subtle piece of conceptual art, smuggled into households as musical instrument, an artwork in disguise.

There’s also something architectural in it — a system of hollow parts, suspended, designed not for use but for possibility. A structure that makes no claim to permanence, but does insist on design. The wind chime is not chaos. It’s an ordered possibility. And the sound it makes is less a performance than a document: evidence of atmosphere.

This is not a grand metaphor. It’s just an object I keep passing and noticing — how it holds silence, how it responds, how it sounds and stops and sounds again. And how, like many structures I admire, it is defined not by what it produces, but by what it allows.

Unhappy Readymade (box in a valise version)

https://www.toutfait.com/unmaking_the_museum/Unhappy%20Readymade.html︎︎︎